Revisiting The Art of The Batcave and its Roots in London’s Soho Subculture

A look back at the iconic Batcave club and its connection to generations of subculture before it in London’s Soho.

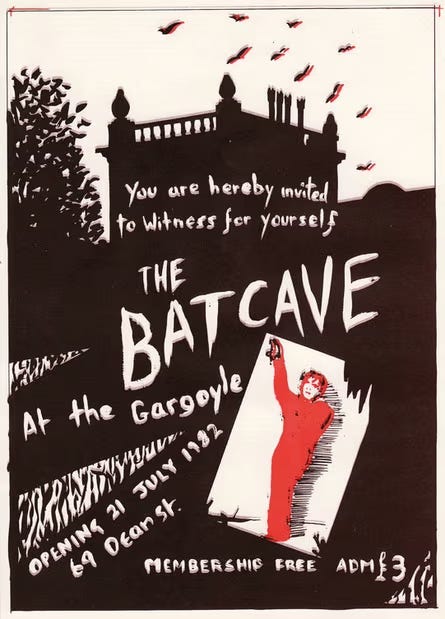

In this first installment of a series called Venues, we cover the places that have become legendary in subcultures for their impact on music, fashion, and community. This series endeavors to look at why specific spaces and events have become so memorable and symbolic of their moment in time. If we’re lucky, we can use the knowledge of these past successful venues to inspire the creation of new spaces that nurture the underground and most vitally, the art and artists that frequent these spaces. We begin the Venues series with one of the most beloved and referenced of the ‘80s, the London weekly called The Batcave.

Approaching a topic like the early ‘80s Batcave club in London’s Soho can be tricky. Why write about an event that has already had so much press and so many online articles dedicated to dissecting the fashion, hair, and makeup of the club’s regulars like Marc Almond, Dave Ball, Nick Cave, Robert Smith, Nik Fiend and Mrs. Fiend of Alien Sex Fiend, Robert Smith, Siouxsie Sioux, and Youth of Killing Joke, among many others? The fixation on the celebrity aspect of the event leaves room to illustrate the deeper impact of The Batcave, the beacon for the new underground emerging from the previous decade’s prevailing genres like disco, punk, glam, hard rock, and folk making way for the darker post-punk and goth genres.

The Batcave and places like it represented a space for people who identified as outsiders to gather and express themselves without fear of persecution or violence. The act of dressing for oneself and for the purpose of being seen meant those who created these avant garde looks were out of step with contemporary trends, let alone society’s ideas of gender and beauty. Venues like The Batcave also represented a democratization of fashion and subcultures in its relaxed door policy, which Batcave co-founder Olli Wisdom was keen to point out to media covering the club’s success. Similar legendary clubs around that time, most notable among them were New York City’s Studio 54 (its original run was from 1977-1980) and London’s Blitz Club (1979-1980), boasted a strict door policy where entry was a symbol of elevated social status. In fairness, all of these clubs promoted a sense of equality among those in attendance, but the attitude about access to that space and the arbiters of that access at Studio 54 and Blitz were far from the open policy of The Batcave. Consequently, the door policy at The Batcave attracted a diverse range of people and defied the stereotype of gatekeeping in dark alternative scenes like goth.

I pay my £3.00 and am confronted by great swoops of grubby netting that stretches from wall to wall. The atmosphere's ideal for mere mortals and pop stars to admire each other's white pan- cake make-up and to sway to music by Siouxsie, The Cure, Alien Sex Fiend and such early '70s Glam Rockers as Sweet and T. Rex. Marc Almond stands arm-in-arm with Nick Cave of The Birthday Party. One Dracula lookalike keeps getting his towering hair-do in the drooping netting. Ollie, lead singer of The Specimen and club host, laughs: "Anything goes! It's all fun and very creative. - Linda Duff. A Night At The Batcave. Smash Hits, March-April 1984.

Soho and Subculture

The Soho neighborhood of The Batcave’s original location at 69 Dean Street has its own fascinating history. A place for bohemians, outsiders, and intellectuals, Soho attracted unique businesses and nightlife, furthering its reputation as a place that stepped outside the boundaries of polite society and stayed relevant by transforming through the decades. The neighborhood itself was built during the reconstruction efforts following 1666’s Great Fire in London, where “Artists quickly adopted the new suburb as London’s fashionable quarter, and the king, Charles II, purportedly visited his mistress ‘pretty, witty’ Nell Gwyn in a house on the site of No 69” (The Face, February 1983). In an interview for The Quietus in 2012, David J of Bauhaus and Love and Rockets described Soho, saying “It had a sort of Dickensian, Jack the Ripper flavor to it, you know, the back streets of Soho. It was dingy and very much had the faded glamour of old Soho. It was romantic in that way, it was easy to project one’s gothic fantasies on that locale.”

By the 1930s the establishment at 69 Dean Street was The Gargoyle Club, a subcultural hotspot for the bright lights of stage and screen, including the English playwright, director, actor, and composer known as The Master, Noël Coward. Given the nature of Coward’s reputation as a creative pioneer, his beloved and subversive works along with his enjoyment of nightlife at venues such as The Gargoyle Club, it is fitting to note how his career pushed social and moral boundaries that reflected the societal changes around him. This boundary-pushing has become a central part of Coward’s legacy, as was eloquently summarized by a BBC retrospective, saying “The Master may have hidden always behind a mask, but he was also hiding in plain sight – continually using his plays to remind audiences of the roles he played, the masks he wore. Consider this line from Leo, another character close to a self-portrait, in Design for Living: ‘It's all a question of masks, really… we all wear them as a form of protection; modern life forces us to.’”

Soho and places like The Gargoyle Club were spaces for creatives like Coward to nurture ideas and witness others pushing their own creative boundaries through performance art and music. Naturally, the fine arts world has a connection to the club, as noted in an article by The Face (February 1983), saying “The rooftop Gargoyle club at 69 Dean Street opened in 1925, boasting the French painter Henri Matisse not only as a member but as the inspiration for the Moorish interior of its ballroom – a steel and brass staircase was still in evidence when the Comedy Store took over the club in 1979.”

Coffee bars represented a new social order for post-WWII London where socioeconomic and gender barriers began to change, lending to what we now think of as the subcultural melting pot that Soho represented. These were more than a fad for teens to get out of the house and caffeinate themselves with espresso instead of whatever was available in their home; coffee bars were attractive to creative types in the 1950s because they stayed open later and were all-ages. Importantly, women could feel less intimidated in a coffee bar versus a pub and live music was hosted at coffee bars in addition to jukeboxes that brought recorded music to spaces that once solely relied upon live music to provide entertainment and ambiance. Consider that 45rpm singles debuted in 1948, exponentially expanding the popularity of the jukebox and its eventual evolution to the club DJ.

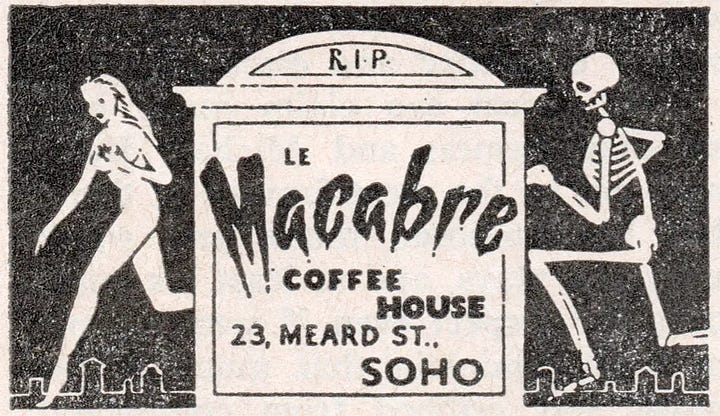

A notable coffee bar in Soho during this era was Le Macabre Club, an obvious predecessor to The Batcave in theme and décor. Opening in 1957 and closing sometime in the 1970s, Le Macabre Club took influence from the notorious horror-themed Théâtre du Grand-Guignol (The Grand Guignol Theatre) in Paris as well as other ‘death cafés’ in Europe. An excerpt from an article in The Telegraph (2017) describes Le Macabre Club’s atmosphere: “The tar-coloured walls would be adorned with plastic skeletons, painted cobwebs, and frescoes of naked women twirled in the moonlight by libidinous ghouls. You’d see hip teenagers (‘cats’, as they were known) wearing sunglasses, sipping espresso, and debating the ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre and the jazz of Dizzy Gillespie on the coffins, punctuated by the odd guitar jam…” In an interview with The Look in 2000, Glen Matlock of The Sex Pistols described his experience at the famed Soho coffee bar, saying “When I started working as the Saturday boy at Let It Rock [in 1973], Malcolm McLaren used to take me around these strange places which played a part in early rock & roll. One time we went to Le Macabre. I don’t know how he knew about it, but it was the real thing. The tables were coffin lids and the jukebox only had songs to do with death.”

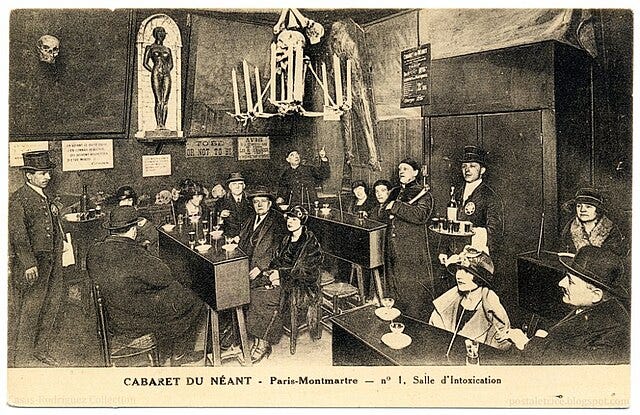

The roots of this uniquely morbid social gathering place also traces back to the cafes of Paris in the early 1890s such as the Cabaret du Néant (“Cabaret of Nothingness"/"Cabaret of the Void”) which featured the same coffin-shaped tables as well as (human) bone chandeliers in the various rooms of the venue, like The Vault of Sad Ghosts and Intoxication Hall. The Batcave even had a notice posted above the door that was referential to that of Cabaret du Néant’s entry sign which read “Enter, mortals of this sinful world, enter into the mists and shadows of eternity. Select your coffins, to the right, to the left; fit yourselves comfortably to them, and repose in the solemnity and tranquillity of death; and may God have mercy on your souls!” The Cabaret du Néant along with The Gargoyle Club and Le Macabre Club were definitively goth before the term became colloquially known.

By the ‘80s The Batcave became the beacon for other similar-minded clubs to follow, celebrating the emerging scene that rose after many young people thought ’77 punk had become a parody of itself and the New Romantic scene had gone commercial. The Batcave positioned itself as a meeting place for friends as well a launching pad for bands, attracting a diverse range of people. The same fate awaited the scene that blossomed at The Batcave as it did for those that came before it, but the mystique of this campy, ghoulish weekly event in Soho is still evident in the deathrock and goth scene today.